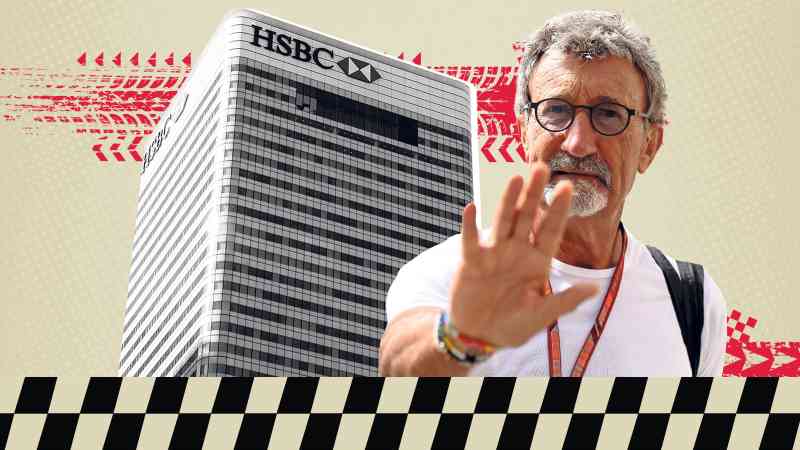

Eddie Jordan is suing HSBC for allegedly encouraging him to borrow £47 million to invest in a “low-risk” fund that lost him £5 million.

The former Formula 1 boss’s investment company, Pendragon Investment Holdings, claims that advisers at HSBC’s private bank put pressure on it to invest in the HSBC GIF Global Credit Floating Rate bond fund between 2019 and 2023. The fund was presented as having only a 1 per cent chance of loss in the worst-case scenario.

Jordan did not realise that the fund invested in high-risk sectors including the Chinese property market as well as in Zimbabwe, Russia and Turkey.

The fund lost about 10 per cent of its value when it matured at the end of last year. Meanwhile, HSBC made £4.2 million in management fees and interest on Jordan’s loan, which was used to make the investment.

The case, which was brought to the High Court in London last month, exposes the problem of financial advisers recommending complex products that are marketed as low risk but can be much more volatile than expected.

Complaints regarding mis-selling and the suitability of financial advice increased from 570 in the 2021-22 financial year to 884 in 2022-23, according to analysis of data from the Financial Ombudsman Service by the firm Oxford Risk. The ombudsman found in favour of the complainant in 62 per cent of cases in 2022-23, up from 49 per cent the previous year.

Oxford Risk expects the number of complaints to have reached a record high in the past tax year after tougher rules protecting consumers were introduced by the regulator, known as the “consumer duty”.

The Jordan case also highlights the problem of investing in products recommended by an adviser tied to a particular firm. It is best to use an independent financial adviser who can consider products from a wide range of companies.

Jordan has been a customer of HSBC Private Bank since 2009.

In May 2019 the bank provided a presentation to Pendragon, recommending an investment in the HSBC GIF Global Credit Floating Rate bond fund. It invested in bonds issued by companies around the world — these bonds are effectively IOUs, where a company borrows money from investors for a set period, paying them a regular income over that time and returning their money at the end. They are generally regarded as being less risky than company shares.

The HSBC fund had a minimum investment of £5,000 and was presented as “low risk”, according to court papers seen by Money. The four-year investment would pay an annual income of about 5.25 per cent with charges of 0.33 per cent a year, with the original investment returned on maturity.

Before agreeing to invest, Pendragon emphasised that it would tolerate a loss of only 1 per cent. HSBC said the primary objective of the fund was “capital preservation”. In conversations and emails to Pendragon around June 2019, HSBC said the fund could “theoretically lose 0.35 per cent” and in a “stressed scenario”, such as the 2008 financial crisis, this could increase to 0.98 per cent. Losses beyond 1 per cent would not occur, it said.

• HSBC was no help when I lost £120k in a Christmas scam

Pendragon had a so-called Lombard loans facility with HSBC’s private bank. This is a type of loan offered to wealthy people, which is secured against their liquid assets — typically shares and bonds.

Warning that the investment was at risk of being “oversubscribed”, HSBC recommended that Pendragon borrow £66.7 million to make the investment.

Jordan’s company ended up investing £46.9 million. HSBC would earn £1.3 million in management fees on this investment over the four-year period, plus £2.9 million in interest on the loan it provided to make the investment.

It later turned out the investment was not oversubscribed. While the fund was open to all investors, the last company factsheet from October 2023 shows it had $261.7 million (£206.2 million) invested, suggesting that Jordan’s investment accounted for almost a quarter of its assets.

Pendragon claims that HSBC’s presentation and emails, which did not mention the fund’s exposure to markets such as Russia, Turkey and Zimbabwe, provided “false” statements and the bank had “no reasonable grounds for believing them and/or was negligent in making them”.

As the fund started to lose value, Pendragon made repeated inquiries about its performance, particularly during the Covid outbreak in 2020.

HSBC provided assurances, including saying that the losses were due to a “mathematical” error that would be rectified. It urged Pendragon to stick with the investment until maturity and warned that an early exit would result in a 0.35 per cent penalty.

According to court papers, the fund was down 10 per cent between June 2019 and June 2023. By contrast, a “higher risk” emerging market fund, the Blackrock Emerging Bond ETF, was down only 2 per cent over the same period, according to a submission by Pendragon in court.

Pendragon argues that if HSBC had acted with “reasonable care and skill”, it would have advised Pendragon to close the investment around September 2019, when there was some significant loss of capital, or again in February 2020, when the risks of Covid became clear. Had the investment been closed at that point, its losses would have been about 1 per cent.

Jordan is seeking £4.94 million from the bank, which is the difference between what the bond was worth at maturity and what he invested. The claim discounts the income Jordan made from the bond, which was more than offset by the interest and charges he paid to HSBC.

• HSBC error left me with no money to pay for Mum’s funeral

HSBC declined to comment. It has 14 days to respond to the claims lodged in court. A request for comment was also made to lawyers representing Pendragon as well as to Jordan.

Paul Angell from the investment platform AJ Bell said: “While the vast majority of investors are unlikely to be solicited into a fund such as this, it is a good warning that you should never feel obligated or pressured to make an investment, especially ones you do not understand.

“Recommended buy lists provided by reputable investment firms can be a good way for investors to narrow the field. These lists typically account for the calibre of management teams, past performance, price and fund size among other considerations.”

• HSBC chairman Mark Tucker knighted in King’s birthday honours

A good financial adviser will never put pressure on you to make an investment decision quickly. Always ask about the details of a product, its charges and the risks. You should also agree on what fee the adviser will take before making any investment.

Your adviser should also provide you with a suitability letter, which is a regulatory requirement. This sets out the advice you received and the reasons for the recommendations made. If you disagree with the reasoning or do not understand, ask further questions before approving an investment.

If you use a discretionary fund management service, where an adviser makes investment decisions on your behalf, make sure you are happy with the level of risk you have asked the fund manager to take. This is normally determined through questionnaires and interviews at the start of your relationship with the adviser.